Keep yourself updated by liking our Facebook page, where we regularly upload photos, videos, and more!

Welcome to this page that focusses on the problem of light pollution in the Maltese Archipelago.

This page was designed with the general public and the media in mind, and accompanies the first major scientific study on light pollution in Malta, published in the Journal of Environmental Management.

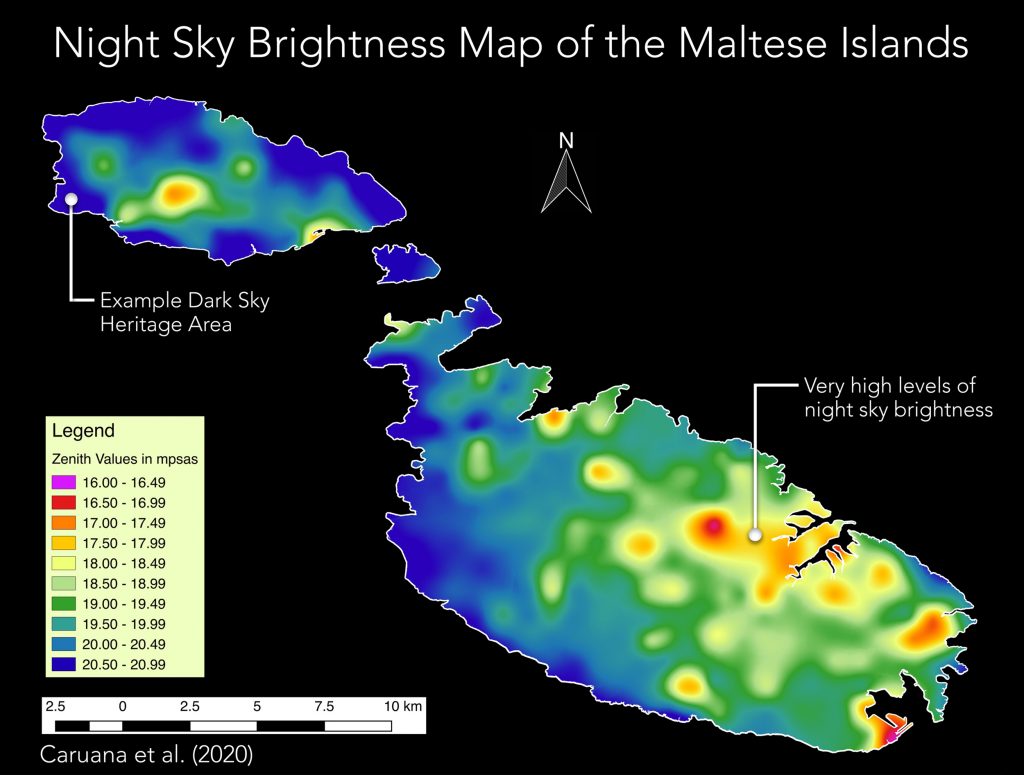

Titled `A Photometric Mapping of the Night Sky Brightness of the Maltese Islands‘ (Caruana et al. 2020), the study investigates the brightness of the night sky in Malta, and discusses the effects of light pollution, in particular on astronomy, ecology and human health.

Resources

The below thumbnails provide direct links to various resources related to this publication

The main figure showing a map of the night sky brightness over the Maltese Islands, illustrating the distribution of light pollution, is found at the top of this page.

Any questions should be directed to the corresponding author, Prof Joseph Caruana, by clicking here.

What does the above map show?

The map shown above illustrates how bright the sky looks from different areas on the Maltese Islands. Red is the brightest, followed by orange, yellow, green and blue. Dark blue represents the darkest sites on the Islands.

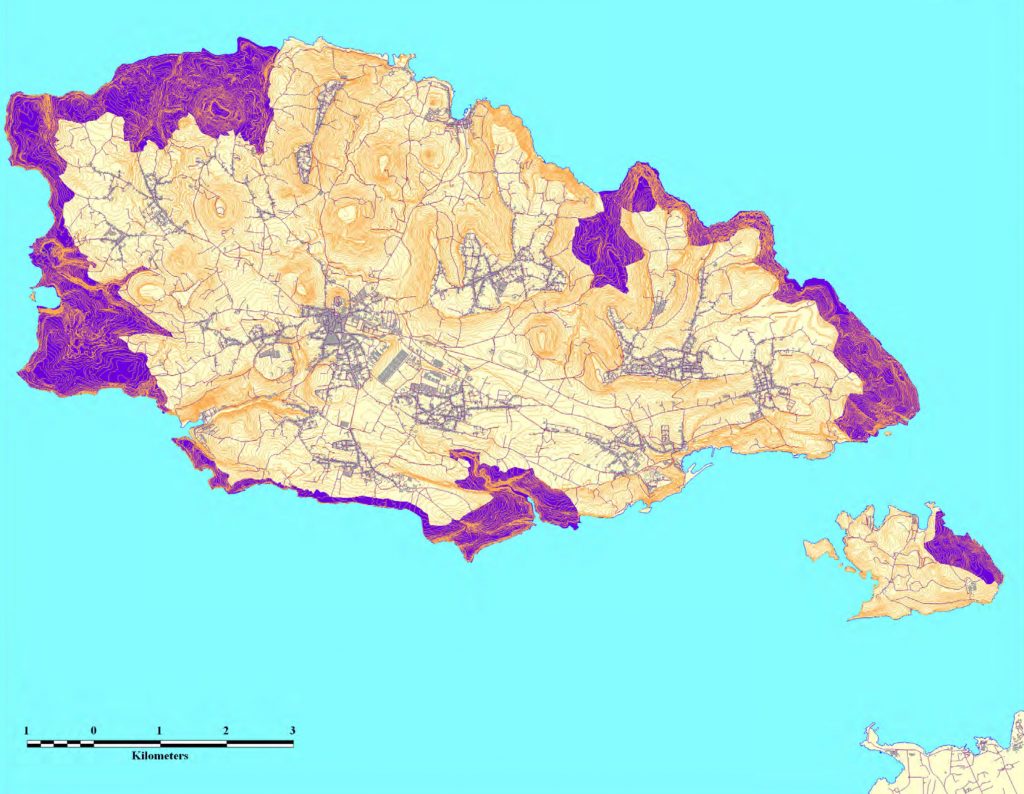

Many of the darker sites are situated within existing Dark Sky Heritage Areas (DSHAs) in Gozo and Comino. These are coastal zones that were designated by this title in the Malta Environment and Planning Authority (MEPA) Gozo and Comino Local Plan (2006) in order to recognise their darker skies and thereby conserve them.

These designated DSHAs are denoted in purple in the figure on the right. The Gozo and Comino Local Plan states that for such sites:

“Where relevant, reflective signs shall be employed to guide driving at night, whilst the installation of lighting which is not related to aerial or maritime navigation, shall be strongly discouraged.“

How is this map different from what is shown in images from space?

The two approaches complement each other. The view from the ground is affected by backscattering of light by air and other particles (e.g. aerosols) as well as other environmental factors, and it therefore represents what one would perceive when looking up.

How was this map created?

It involved a lot of work over a number of years. The three main islands of Malta, Gozo and Comino were divided by means of a 1 km-squared grid. In this manner, the Islands were divided in a total of 347 individual grid-cells. Multiple measurements of the sky’s brightness at night were painstakingly recorded in each of these cells to create the above map. In order for such measurements to be taken, the scientists had to wait for clear skies (i.e. no clouds) and times when there was no moonlight. Otherwise, the representation would not be correct. Following the accumulation of this data, a mathematical algorithm was used to create the smooth map.

What, exactly, is Light Pollution?

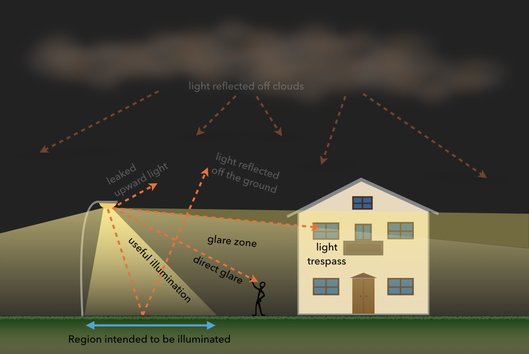

Put simply, light pollution is the result of any artificial light that is brighter than required, misdirected such that it spills onto areas which are not intended to be illuminated, and intrusive. Very often it is the result of poorly designed lighting fixtures or ill-thought lighting plans.

Looking at the diagram to the right serves to highlight some of the main problems we often encounter. In this illustration, the region on the ground intended to be illuminated is marked. However, note how some light is leaking upwards to the sky, some finds its way into the eyes of passersby causing glare, and some even trespasses into people’s home(s).

What are the effects of light pollution? Is it only relevant for astronomy?

Light pollution’s effects go beyond hampering astronomical observations. We could mention three main areas where light pollution is known to have an impact.

Astronomy

For purposes of astronomy, any light that finds its way to the sky is problematic. Whether light is leaked directly towards the sky or whether it reflects off the ground and sent skywards, it creates skyglow that hampers our views of our beautiful universe. Humankind has observed and drawn inspiration from the night sky for thousands of years. Eroding such views would therefore represent the elimination of a cultural cornerstone of humanity. Further to astronomy, however, light pollution has other serious effects, as we shall see below.

Ecology

We know that light pollution poses a threat to ecology. From dragonflies and bees to birds and turtles, numerous species are impacted by light pollution. A local example of a species affected by light pollution is the cliff-nesting Shearwaters.

Human Health

Studies are also showing that light pollution can have adverse effects upon human health, linked to issues ranging from psychological well-being to various forms of cancer, in particular via the suppression of a hormone called Melatonin. Blue light seems to have a larger effect in this regard. It also disrupts the body’s circadian rhythm, i.e. the body’s natural sleep-wake cycle.

Are there different types of light pollution?

Yes, and they have been briefly touched upon above. The main types are three:

1) SKYGLOW, which represents the overall brightness of the night sky.

2) GLARE, which is light shining directly in people’s eyes, and which can cause discomfort and create hazardous situations (e.g. when driving).

3) LIGHT TRESPASS, which is when light enters places where it should not, such as people’s homes.

What are the main sources of light pollution?

Churches, public monuments, gardens, squares, and shops. Most sources of light pollution can be mitigated; all it takes is commitment. Light pollution is a reversible problem.

Which are the worst zones in Malta? And what about Gozo?

In Malta, the worst situation is in Birkirkara. In Gozo, it is Victoria (the Island’s capital) closely followed by Għajnsielem. We expect Għajnsielem to have become even worse since the time these readings were acquired due to the proliferation of additional lighting. More measurements are currently being undertaken to assess and monitor the situation.

And which are the best?

In Malta, the best site is Rdum tal-Vigarju (cliffs off Baħrija, limits of Rabat). In Gozo, the best site is Ta’ Ħarrux (off Dwejra, limits of San Lawrenz).

Is the situation becoming better or worse?

Unfortunately, at present, the data indicate that light pollution is on the increase. Light pollution seems to be getting worse in Malta, and certain specific locations exhibit a very marked level of increase in the night sky brightness between two given years.

I recently read that an astronomical observatory will be set up in Gozo. Would this not be affected by light pollution?

While certain astronomical observations will be hampered and others rendered impossible because of currently existing light pollution levels on the Islands, there is still a good number of projects that can be successfully pursued. The specific site was chosen on the basis of it being one of the darkest available sites.

Moreover, not all astronomical observations are carried out within the window of visible light, which is the region of the electromagnetic spectrum where the problem is the most serious.

In summary then, while light pollution is of major concern for astronomy, the specific site was chosen due to the fact that it is one of the best available sites on the Islands and allows for some important work to be carried out. We should continue in our strive to lower light pollution levels across the entire archipelago.

I read / people told me / I was under the impression that there is no light pollution at the chosen observatory site. But this study states that no site is pristine. Is this not somewhat contradictory?

No site on the Maltese Islands can be said to be pristine, because for a site to be worthy of such a title, the night sky has to reach natural darkness. None of the sites on the Maltese Islands exhibit this level of darkness. However, light pollution at the observatory site in Nadur, which is a Dark Sky Heritage Area, is significantly lower than in other regions on the Islands, especially looking towards the north. So a correct statement would be that there is far less light pollution at this site than in other zones. In other words, if someone told you (or you read somewhere) that there is no light pollution whatsoever at the Isopu site in Nadur, then the information was not conveyed correctly.

The area of Ta' Ħarrux, just off Dwejra, was found to be the darkest site. What sort of views can one obtain from Dwejra?

You may find a short video-clip with examples of images obtained from this site by clicking here.

A small selection of images may also be viewed here.

If Dwejra is still the darkest site, why not set up an astronomical observatory there?

Indeed, Dwejra is still the darkest site. Looking directly upwards, however, the sky brightness of the chosen site for the observatory is very similar to that of Dwejra’s. Looking towards the South, Dwejra is the undisputed winner as one would be facing seaward, away from light pollution originating from land. For views to the north, however, the site in Nadur is better for the same reason.

In addition to these considerations, there were other technical reasons for the site selection, e.g. the very proximity to the sea in the case of Dwejra, which can cause maintenance issues with the equipment, issues pertaining to communication for remote operation of the observatory, as well as practical concerns in terms of where to locate the telescope itself. (Needless to say, human intervention at Dwejra, a very sensitive site, should be minimal in all respects.)

So is it still important to conserve Dwejra's night sky?

Absolutely! It offers the best views of the southern sky. But it is just as important to conserve all other Dark Sky Heritage Areas and work to lower light pollution overall across the entire archipelago.

Given that Dwejra is still so dark, is it safe to assume there is nothing to worry about?

Unfortunately this is not the case. Despite it being the darkest site, we find three sources of light pollution at play in Dwejra, without which the site would be far better.

1. The first source of pollution is at the site itself or very close-by. Sporadic lighting (which should not be present to begin with since Dwejra is a Dark Sky Heritage Area) causes major problems; specific cases were measured to brighten the night sky by more than double.

2. Lighting fixtures installed at the public square of the village of San Lawrenz (within whose confines Dwejra is situated), are badly designed, and a great source of light pollution.

3. Unchecked lighting on the rest of Gozo is encroaching upon Dwejra, adversely affecting north-eastern to eastern views especially.

So what is the solution for Dwejra?

The solution is three-fold:

- Lighting on site should not be allowed, in accordance with the regulations applying to Dark Sky Heritage Areas.

- Lighting in nearby zones should be closely monitored by the authorities. Only properly designed and necessary lighting should be in place. Close-by villages especially should utilise best lighting practices to help preserve this special site. Local Councils can help with certain aspects in this regard. There should be strict attention to this issue past a certain time, e.g. 11pm.

- A light pollution strategy that addresses the entire island (in fact, all islands) is direly needed in order to properly mitigate light pollution.

How can light pollution be reduced in general?

There are a number of ways in which this can be achieved locally. The solution to lower light pollution levels is not to switch off all lights and stay in darkness! Below we list but only six examples of how light pollution can be mitigated:

- Firstly, as already stressed above, there is a need for a nation-wide policy to regulate the use of outdoor lighting. There should be clear regulations about what sort of lighting is allowed and where.

- All external lighting should consist of full cutoff lighting, which efficiently directs light only downwards, towards the ground.

- Lighting should not be brighter than is required.

- Road lighting should employ warmer lighting fixtures than the current >4000K (i.e. blue-rich) lights which are used in Gozo, for example. Blue-rich light scatters more and its effects are worse. Smart lighting should also be considered, whereby lights are turned on only when required. Certain roads, e.g. remote countryside ways, are not used as frequently at night, so these do not have to be constantly illuminated all night long. Fixtures equipped with sensors can switch on these lights as required upon the approach of vehicles, and where appropriate, reflectors can be used instead.

- Churches and public monuments are two main culprits in Malta and Gozo. Very badly designed lights are prevalent all over the Islands, and these are switched on all night long. Rarely does one stop to appreciate a statue or a church’s facade at 3am in the morning, so more intelligent schemes would be far more appropriate. Entities including the Government and the Church Environment Commission should be much more proactive in this regard.

- Public squares and gardens should employ full cut-off lighting that directs light where it is required, i.e. the ground. Globe-lighting and other poor designs have no place in the modern day, when so many alternative solutions are available. There is really no excuse.

- Terminal buildings (e.g. in harbour areas) require adequate lighting for navigation and safety reasons. However, good lighting practices can still be employed. Excessively bright lighting emanating in every direction does not translate into good or helpful lighting. To the contrary, it can result in such high levels of glare that it actually creates a hazard. Even in such areas, following good lighting practice is important.

What can I do to help?

There are a number of ways in which you may help with lowering (or, at the very least, not increasing) light pollution.

- Do not install lighting where it is not required. Before you put a light in your garden, for example, think about whether this is really required. Or perhaps you can install a lighting fixture that is motion-triggered instead, so that it is not switched on for a long time. Ask yourself if that ornamental light on your house’s or apartment’s facade is really required. Make sure any required outdoor lighting is properly shielded. Every little bit helps. Light knows no boundaries, and light pollution is the accumulation of all such light.

- Speak to your local council. It is important that citizens make their voices heard. If there is bad lighting in a zone near you – perhaps even trespassing into your own home – and it falls under the remit of your local council, speak up.

- Spread the word! While many are aware of other forms of pollution (e.g. air or water), light’s pollutant attributes are still not as well known. Awareness is increasing, but it is certainly not enough yet. You can help inform others, young and old alike. Education is key.

Where I can learn more?

- We upload regular updates to our Facebook page.

- The website of the International Dark Skies Association is a great resource where you may read more about light pollution, its effects, and how to mitigate it.

- Globe at night is a good place to learn about citizen science, i.e. how you can contribute your own observations.

Media Coverage

Below follows a sample of articles / features related to this study (and light pollution in Malta in general) that appeared in the media.

- Podcast by the GRDA (2023)

- Article in the Times of Malta (2021)

- Interview in the Malta Independent (2020)

- Feature in the Times of Malta (2020)

- Feature in Malta Today (2020)

- Video feature and interview on TVM news bulletin (2020)

- University of Malta Newspoint Feature (2020)

- Article in THINK magazine (2019)

- Article in THINK magazine (2018)